It all started with a dream—a vision of space battles, alien worlds, and a grand mythological tale that could capture the imagination of an entire generation. In the early 1970s, George Lucas was just another young filmmaker with big ideas but little influence in Hollywood.

Fresh off the success of American Graffiti (1973), Lucas had an obsession with old adventure serials like Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers—stories of intergalactic heroism that he wanted to bring into the modern age.

Lucas had originally tried to acquire the rights to Flash Gordon, hoping to remake it for the big screen.

But when he was denied, he did what any visionary would do—he set out to create his own universe. Inspired by mythology, Akira Kurosawa’s The Hidden Fortress, and Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Lucas began writing a sprawling space epic that would borrow from classic storytelling structures but introduce something completely new.

The first drafts of Star Wars were wildly different from what would eventually hit theaters. The script was a dense, complicated mess, filled with endless world-building, unpronounceable names, and a protagonist named Annikin Starkiller. There were no Jedi as we know them, no Death Star, and no clear hero’s journey. Lucas kept revising, cutting, and reshaping the story, trying to mold it into something audiences could connect with.

As he refined the script, Lucas faced an even bigger challenge—convincing a studio to take a chance on his bizarre sci-fi film.

At the time, the industry wasn’t interested in space adventures. Science fiction was seen as a niche market, mostly relegated to B-movies with cheap special effects. When Lucas pitched his idea to major studios, he was met with skepticism and rejection.

Finally, 20th Century Fox took a gamble on him, largely because of the unexpected box office success of American Graffiti. Alan Ladd Jr., an executive at Fox, believed in Lucas, even if he didn’t fully understand Star Wars. In 1974, Lucas was given a modest budget and the green light to begin production.

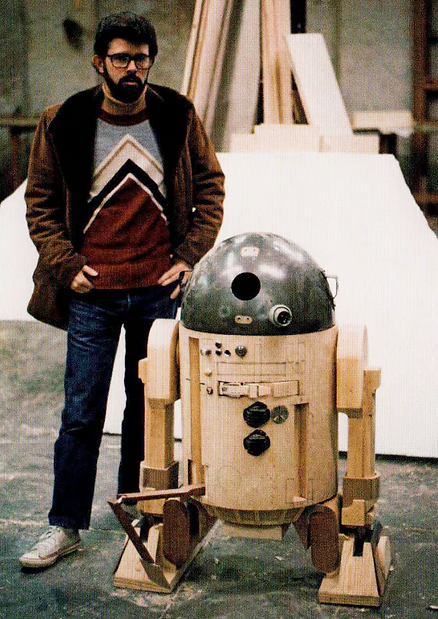

With a studio backing him, Lucas assembled a team to bring his vision to life. He hired concept artist Ralph McQuarrie, who transformed Lucas’s vague ideas into breathtaking artwork—paintings of starships, droids, and desert planets that would become the foundation of the Star Wars aesthetic. McQuarrie’s designs helped Lucas sell the film to skeptics, proving that this world could truly exist.

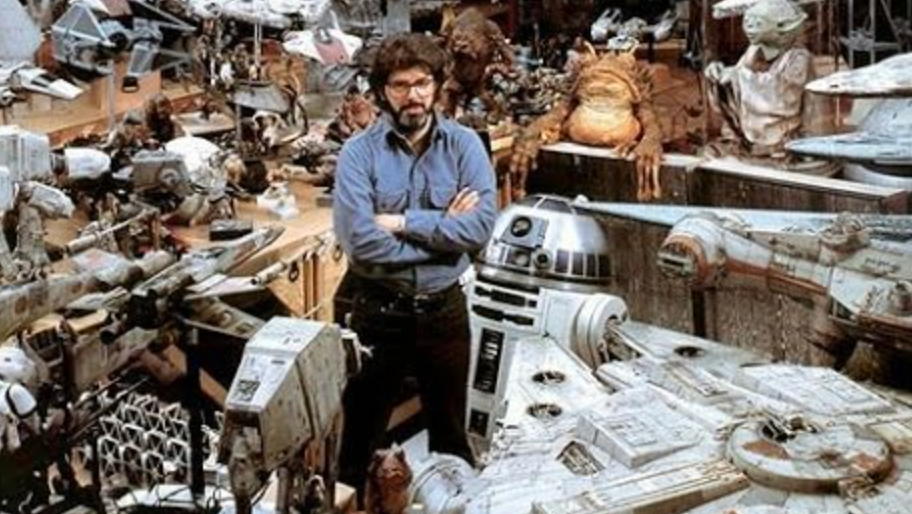

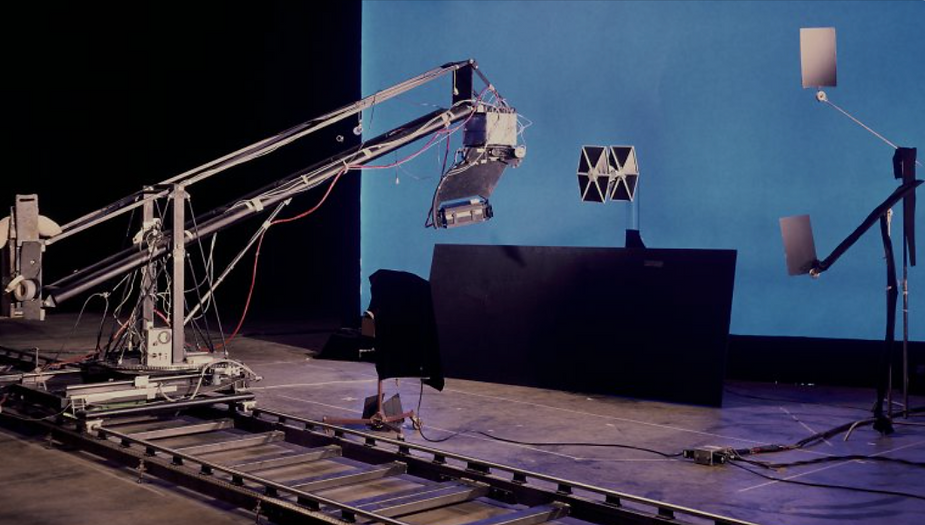

At the same time, Lucas co-founded Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), a special effects company built from scratch to invent the visual techniques needed to make Star Wars feel real. Motion-controlled cameras, miniatures, and groundbreaking effects would be required to make Lucas’s dream a reality. No one had ever attempted anything like this before.

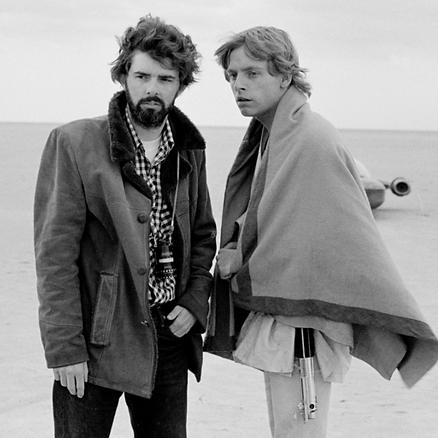

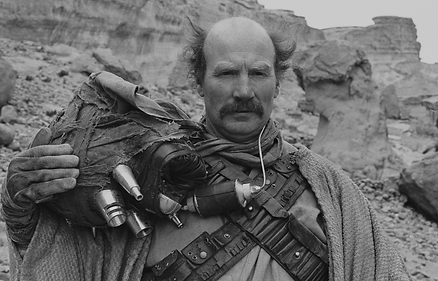

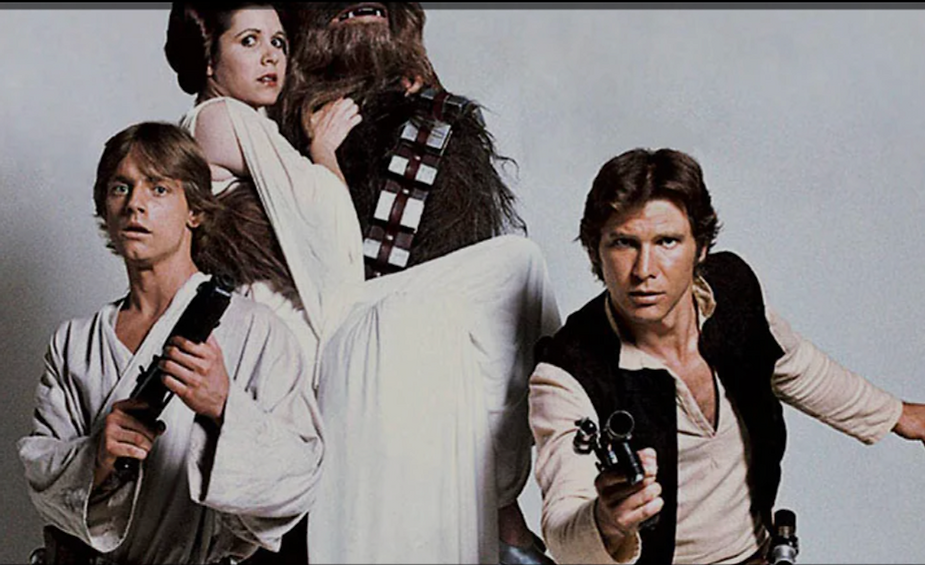

As the film slowly took shape, Lucas needed the perfect cast to carry his story. He sought out unknown actors who could embody the characters with a sense of authenticity.

He found Mark Hamill for the role of the farm boy-turned-hero Luke Skywalker, Carrie Fisher as the bold and witty Princess Leia, and Harrison Ford, a carpenter at the time, as the roguish Han Solo.

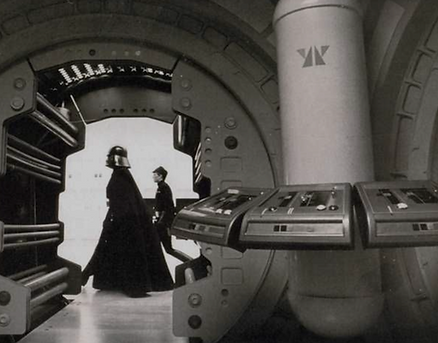

Veteran actor Alec Guinness was brought in as Obi-Wan Kenobi to add some gravitas, while British bodybuilder David Prowse and the deep, resonant voice of James Earl Jones came together to create the iconic villain, Darth Vader.

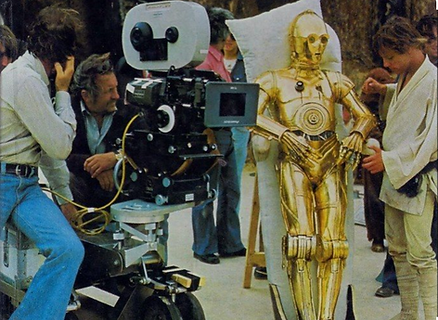

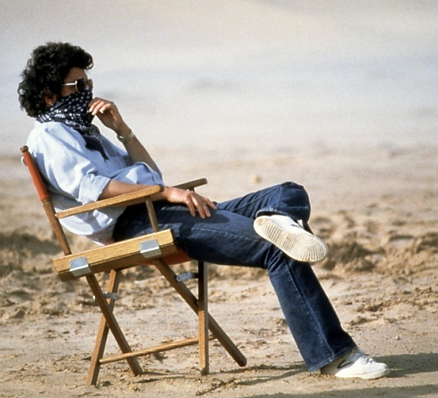

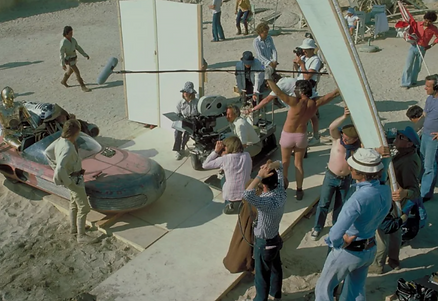

By the time filming began in Tunisia in 1976, everything that could go wrong did go wrong. The desert heat was unbearable, sand got into every piece of equipment, and the remote-controlled droids, including R2-D2, barely functioned.

The British film crew thought the movie was ridiculous, constantly mocking Lucas for his strange ideas. Even the actors weren’t convinced—Harrison Ford famously told Lucas, “You can type this shit, but you sure can’t say it.”

But despite the struggles, Lucas pressed on, obsessively fine-tuning every detail. As the film neared completion, he had to fight to keep his vision intact.

The studio wanted changes, the budget kept ballooning, and Lucas himself suffered from anxiety and exhaustion. Yet, when Star Wars: A New Hope finally hit theaters on May 25, 1977, it became an instant phenomenon—forever changing cinema, pop culture, and the way movies were made.

The crazy vision had become a reality. And the world would never be the same.

Before Star Wars became a cultural phenomenon, it was a filmmaker’s nightmare—a chaotic, uncertain, and exhausting journey that nearly broke George Lucas and his team.

The early stages of production were filled with rejection, budget constraints, technical disasters, and skepticism from nearly everyone involved. But through perseverance, innovation, and sheer willpower, Lucas and his team overcame the odds to create what would become one of the most iconic films of all time.

In the early 1970s, George Lucas had a dream: to make a space fantasy unlike anything ever seen before. He was inspired by old adventure serials like Flash Gordon, the mythology of Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces, and Akira Kurosawa’s film The Hidden Fortress.

But there was one problem—nobody in Hollywood wanted it.

Lucas pitched his story to multiple studios, but science fiction was considered box-office poison at the time.

The genre was either seen as too niche or stuck in the cheap B-movie era of the 1950s. Even when Lucas landed a deal with 20th Century Fox, the studio remained skeptical.

They only took the risk because his previous film, American Graffiti, had been a surprise hit. The budget was originally set at $8 million, which was modest for such an ambitious project.

Even with financing, Lucas faced another massive challenge—his own script.

The earliest drafts of Star Wars were nearly unrecognizable. The story was cluttered with overcomplicated plots, strange alien names, and no clear hero’s journey. Luke Skywalker was originally “Annikin Starkiller,” Han Solo was a giant green alien, and the Jedi (then called the Jedi-Bendu) had a completely different backstory.

Lucas struggled to simplify his sprawling vision. He went through multiple rewrites, each one tightening the narrative, refining the characters, and making the story more relatable. It wasn’t until the third draft that familiar elements like Luke as a farm boy, Darth Vader as a menacing villain, and the Death Star battle took shape. Even then, it was still a tough sell.

As the script evolved, Lucas found inspiration from an unexpected source—concept artist Ralph McQuarrie.

Lucas knew he needed visuals to sell his vision. He hired Ralph McQuarrie, a talented concept artist, to paint key scenes from the script. These included:

These paintings changed everything. They helped Lucas convince 20th Century Fox executives that the film had real potential. Without McQuarrie’s art, Star Wars might have never been greenlit.

But even after securing funding, the production quickly spiraled into one disaster after another.

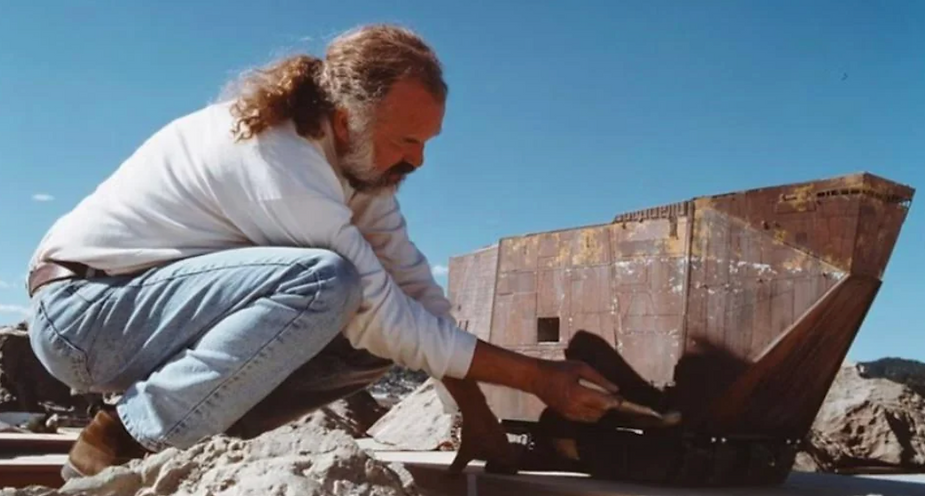

Filming began in March 1976 in the deserts of Tunisia, which would serve as the planet Tatooine. Almost immediately, everything went wrong:

Lucas, already a quiet and reserved director, became increasingly stressed and withdrawn. He struggled to get the performances he wanted, and his direction—focused on visuals rather than acting—frustrated his cast. Harrison Ford famously told him, "You can type this shit, but you sure can’t say it."

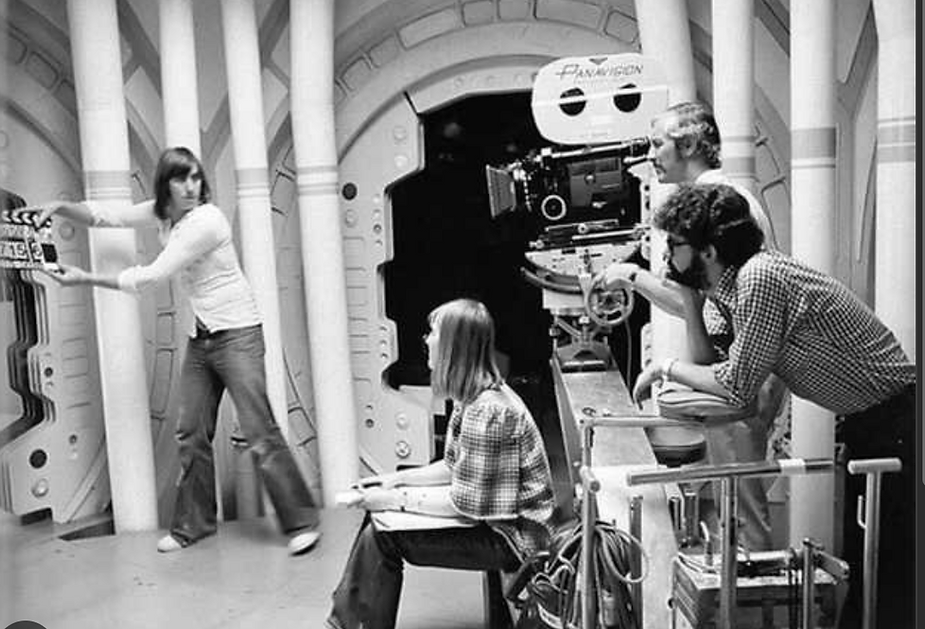

As production moved to Elstree Studios in England, things didn’t get much better.

The biggest problem? Star Wars required groundbreaking special effects—and no one knew how to make them.

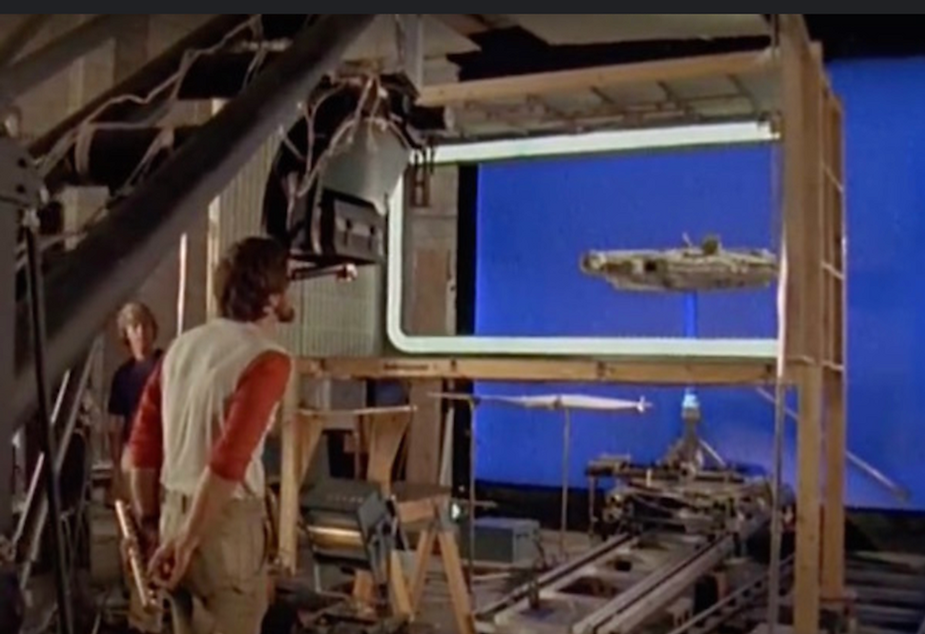

Lucas had assembled a new company, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), but they were essentially inventing new technology from scratch. The team, led by John Dykstra, experimented with motion-controlled cameras, miniatures, and blue screen effects—all of which were unproven at the time.

The biggest disaster came when Lucas checked in on ILM’s progress. After spending half their budget, they had only one usable shot. Furious, Lucas demanded they overhaul everything, putting enormous pressure on the team to deliver.

The Millennium Falcon’s design had to be redone after it was deemed too similar to the ship from Space: 1999.The lightsaber effects were a nightmare—early versions had actual rotating rods covered in reflective material, which failed on camera.The spaceship battles were incredibly difficult to film, requiring ILM to create an entirely new method of shooting miniatures.

With delays piling up and Lucas feeling the pressure, his health took a toll. He began suffering from hypertension and anxiety, and doctors warned him that he was at risk of a heart attack if he didn’t slow down.

Despite all this, Star Wars was finally coming together.

After the unexpected, earth-shattering success of Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), George Lucas found himself at a crossroads.

He had pulled off the impossible—reviving science fiction cinema, breaking box office records, and proving that visual effects could be pushed beyond what anyone thought possible. But he wasn’t satisfied.

With sequels on the horizon and Hollywood clamoring for more, Lucas knew that to bring his full vision to life, he needed to revolutionize filmmaking itself. This meant expanding his fledgling special effects company, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), and turning it into the most innovative effects house on the planet.

What followed was a journey of bold ambition, groundbreaking technology, and relentless problem-solving—one that changed movies forever.

When Lucas first started working on A New Hope, he quickly realized that the existing Hollywood studios didn’t have the tools or expertise to create the effects he needed.

The film required dynamic spaceship battles, alien creatures, and never-before-seen visuals, but traditional effects houses were still using outdated techniques.

So, Lucas took matters into his own hands.

He assembled a ragtag team of young artists, engineers, and filmmakers, giving them a warehouse in Van Nuys, California, and a simple mission: figure it out.

This team, which became Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), was led by special effects supervisor John Dykstra. They invented new technologies from scratch, including:

While ILM pulled off the effects for A New Hope, it wasn’t without struggle. The team was young, inexperienced, and learning as they went, which led to budget overruns and technical delays.

Lucas himself was often frustrated with their slow progress, and by the end of the film, he restructured ILM, parting ways with John Dykstra and taking greater control.

But the real test for ILM was yet to come.

With The Empire Strikes Back (1980), Lucas wanted to push the limits of visual effects even further.

He moved ILM from Van Nuys to Marin County, California, and brought in a new leadership team, including effects wizard Richard Edlund and model-making genius Dennis Muren.

The film introduced even more complex effects challenges, including:

Despite these advancements, The Empire Strikes Back was a nightmare to produce, going over budget and over schedule. Lucas, who had self-financed the film using profits from A New Hope, was on the brink of financial ruin. But when Empire was released, it became an even bigger hit than its predecessor, proving that Star Wars was not a fluke—it was the future of cinema.

When Star Wars (later retitled A New Hope) hit theaters on May 25, 1977, no one—not even George Lucas—was prepared for what was about to happen.

Lucas had spent four grueling years making Star Wars, dealing with budget overruns, skeptical studio executives, and technical challenges. 20th Century Fox, the studio backing the film, had low expectations, releasing it in just 32 theaters nationwide.

Then, something incredible happened.

Within days, theater owners were scrambling to get more copies of the film. Lines wrapped around city blocks, and screenings were sold out for weeks. Fans kept coming back to watch it again and again.

For perspective, in today’s dollars (adjusted for inflation), A New Hope would have earned over $3 billion, making it one of the biggest box office hits in history.

But while the ticket sales were staggering, the real financial goldmine wasn’t the box office—it was the merchandise.

Before Star Wars, merchandising was an afterthought for Hollywood. Studios made most of their money from ticket sales, and while there were some toys and promotional items for big movies, they were nothing special.

George Lucas, however, saw the future.

When negotiating his contract with 20th Century Fox, Lucas made one of the most brilliant business moves in entertainment history—he took a smaller director's fee in exchange for 100% of the merchandising rights.

Fox executives, thinking merchandise wasn’t a big deal, agreed without a second thought.

This single decision made George Lucas a billionaire.

Nobody anticipated how big Star Wars would be, so there were no toys ready for Christmas 1977.

The demand was so intense that Kenner, the toy company producing the action figures, had to sell an “Early Bird Certificate Package”—a piece of cardboard promising kids that they would get their figures months later when they were finally made.

When the toys finally hit shelves in 1978, they flew off the racks.

And this was just the beginning.

Over the next decades, Star Wars became less about the movies and more about the merchandise.

Everything from video games, lunchboxes, costumes, LEGO sets, and even bedsheets bore the Star Wars logo.

Lucas had single-handedly created the modern movie merchandise industry, inspiring other studios to cash in on toys, shirts, and collectibles for blockbusters like Batman (1989), Jurassic Park (1993), and The Avengers (2012).

Even Disney, who bought Star Wars for $4 billion in 2012, saw the true value of the franchise not in ticket sales, but in merchandise.

Star Wars wasn’t just a box office hit—it was a cultural event.

The film’s success changed Hollywood, proving that:

Thanks to Star Wars, every major franchise today—Marvel, Harry Potter, Pokémon—owes its business model to George Lucas' vision.

And it all started with a small, scrappy movie that Hollywood thought would fail.

When Star Wars IV: A New Hope was released in 1977, it did more than just dominate the box office—it rewrote the rules for science fiction, fantasy, special effects, and franchise filmmaking. What George Lucas created was not just a movie but a new industry standard that continues to influence every major blockbuster today.

Before Star Wars, most sci-fi films were either cold, sterile, or campy B-movies. Lucas changed that by creating a lived-in, fully realized universe—one that felt ancient, used, and full of history.

Lucas turned Star Wars into a modern myth, drawing inspiration from Joseph Campbell's "Hero’s Journey," samurai films, Flash Gordon serials, and westerns—a blend of influences that became a new storytelling standard.

At the time, Hollywood’s special effects were stagnant. The industry had not advanced much since the 1960s, and many studios didn’t see a need to innovate.

Lucas, however, knew that to create Star Wars, he needed a new level of visual effects that didn’t exist yet.

So, he built it himself.

To this day, ILM remains the most important and influential special effects company in Hollywood.

Lucas pioneered the idea that a movie wasn’t just a film—it was a franchise.

Hollywood had never seen a multi-film universe before, and today, every major studio follows the Lucas formula.

After Star Wars became a phenomenon, Lucas realized he wanted nothing to do with the traditional Hollywood system.

By removing himself from Hollywood, Lucas gained total creative control—something most filmmakers only dream of.

To this day, Star Wars IV: A New Hope continues to influence:

Lucas didn’t just make a great sci-fi film—he changed the DNA of modern filmmaking.

Whether it’s a new epic space adventure, a groundbreaking special effects film, or a multi-billion-dollar franchise, every major movie today owes something to Star Wars IV: A New Hope.

After Star Wars turned George Lucas into one of the most powerful filmmakers in the world, he did something unheard of: he left Hollywood behind.

Instead of staying in the industry’s power center, Lucas moved north to Marin County, California, and built a creative empire on his own terms.

His legacy in Northern California isn’t just about Star Wars—it’s about pioneering independent filmmaking, revolutionizing technology, and setting the stage for the future of cinema.

Lucas’ crown jewel is Skywalker Ranch, a 4,700-acre retreat in Marin County that serves as a filmmaker’s paradise.

Built in the early 1980s, the ranch became Lucas’ sanctuary for creativity, technology, and storytelling. It features:

Unlike Hollywood’s studio lots, Skywalker Ranch isn’t about making money—it’s about creating without interference. Lucas designed it as a place where art meets technology, attracting some of the best minds in filmmaking and sound design.

Even today, top directors like Steven Spielberg, Christopher Nolan, and Peter Jackson send their films to Skywalker Sound for final mixing and audio production.

While Star Wars made him rich, Lucas never wanted to be just a director—he wanted complete creative control.

Instead of relying on major studios, he built Lucasfilm into one of the most successful independent production companies of all time.

At its core, Lucasfilm was more than just Star Wars—it became a hub for storytelling, innovation, and digital effects.

For decades, Lucasfilm stood as the gold standard for independent filmmaking—until Lucas sold it to Disney for $4 billion in 2012, ensuring Star Wars would continue for generations.

Lucas knew that traditional special effects weren’t good enough for his vision. So, in 1975, he founded Industrial Light & Magic (ILM)—the most important visual effects company in film history.

Based in the San Francisco Bay Area, ILM:

Without ILM, modern visual effects, CGI creatures, and digital filmmaking wouldn’t exist.

Lucas understood that sound is half the experience of a film. He founded Skywalker Sound, which became the most advanced sound design and mixing facility in the world.

Located at Skywalker Ranch, the company has worked on:

The THX sound system, which Lucas created, became the gold standard for cinematic audio, ensuring every theater sounded as immersive as possible.

Lucas’ Northern California empire even led to the birth of Pixar.

In the early 1980s, Lucasfilm had a small computer graphics division working on digital animation. When Lucas needed to downsize, he sold that division to Steve Jobs in 1986—and it became Pixar Animation Studios.

Without Lucas, there would be no Toy Story, Finding Nemo, or modern CGI animation.

By leaving Hollywood, Lucas:

Even after selling Lucasfilm, his technological breakthroughs,

independent mindset, and creative vision continue to shape Hollywood today.

Lucas didn’t just make movies—he changed how movies are made. And it all happened in Northern California.