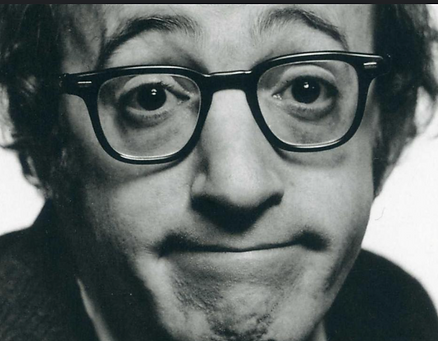

Woody Allen’s journey from a Brooklyn kid to a rising stand-up comedian is a fascinating story of wit, determination, and sheer comedic brilliance.

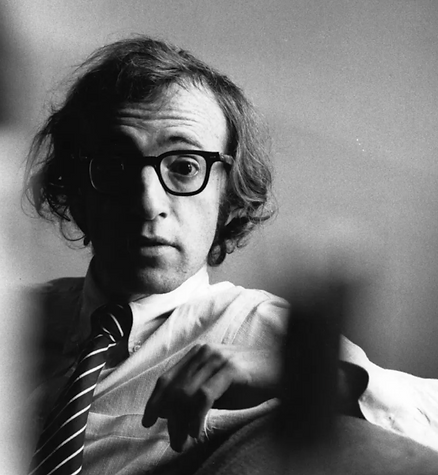

Born as Allan Stewart Konigsberg on December 1, 1935, in Brooklyn, New York, Woody Allen grew up in a Jewish family with a love for movies and humor. As a child, he was more interested in magic tricks and baseball than academics, but his natural ability to craft jokes emerged early.

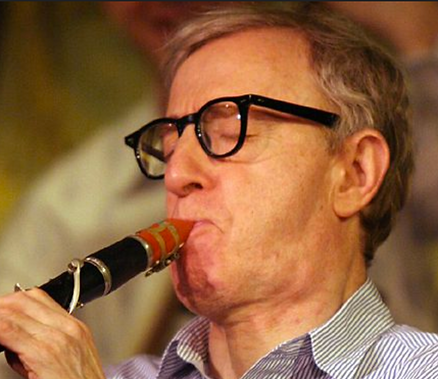

At just 15 years old, he legally changed his name to Heywood "Woody" Allen, inspired by clarinetist Woody Herman. Around the same time, he began submitting jokes to local newspapers and radio shows, quickly making a name for himself as a comedy writer.

By his late teens, Allen was writing jokes for newspaper columns and television shows, including The Ed Sullivan Show and The Tonight Show. His sharp, intellectual humor stood out, and he soon became one of the most sought-after young comedy writers in the industry.

In the late 1950s, he was hired by comedy legend Sid Caesar to write for Your Show of Shows, alongside legends like Mel Brooks and Neil Simon. However, despite his success as a writer, Allen wanted more—he wanted to perform his own material.

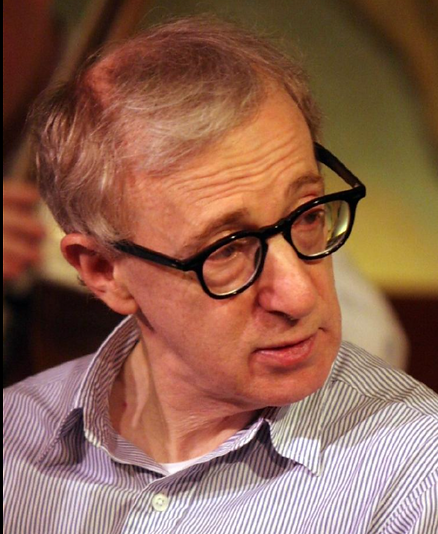

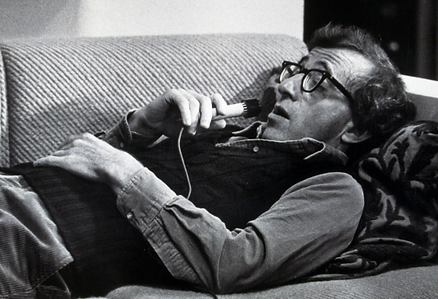

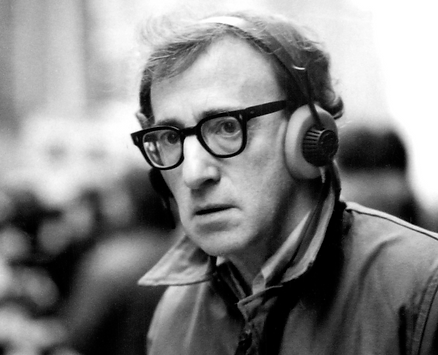

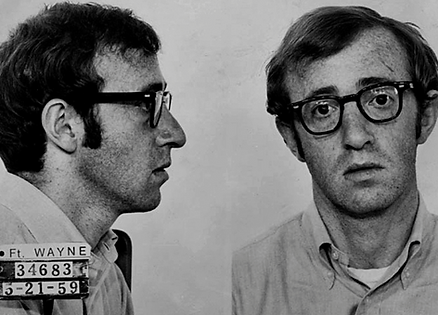

Allen’s transition into stand-up comedy happened in the early 1960s when he started performing at small clubs in Greenwich Village. Unlike the typical comedians of the era, who relied on punchlines and physical humor, Allen pioneered a new kind of stand-up—intellectual, self-deprecating, and neurotic.

His nervous, bookish persona, combined with rapid-fire delivery, made him a standout. He often spoke about existentialism, relationships, psychoanalysis, and his own insecurities, setting himself apart from mainstream comedians.

One of his earliest major gigs was at the Blue Angel nightclub in New York. His breakthrough came when he appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson and began getting national attention. His stand-up career skyrocketed, leading to comedy albums like Woody Allen (1964), which showcased his unique, observational humor.

His success in stand-up paved the way for screenwriting and acting, leading to films like What’s New Pussycat? (1965) and his directorial debut with Take the Money and Run (1969). From there, he would go on to become one of the most influential filmmakers of all time.

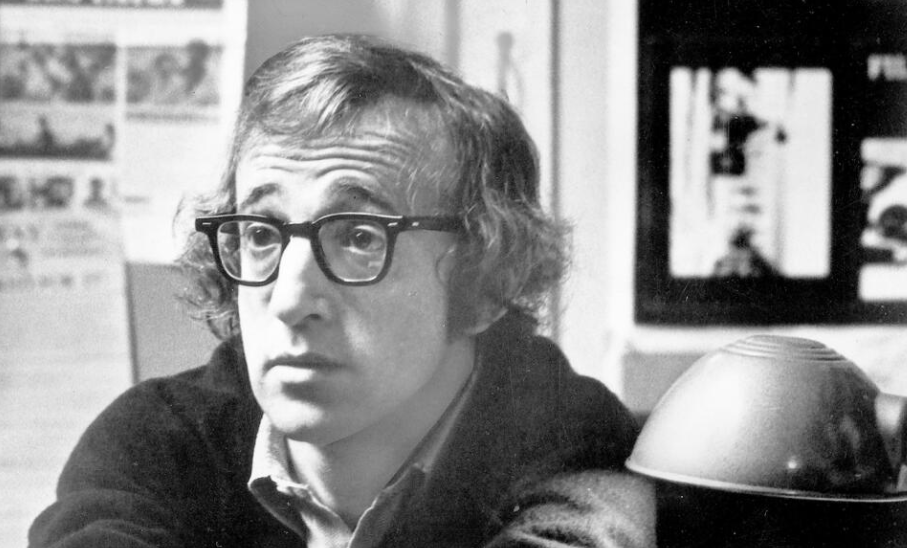

By the early 1960s, Woody Allen had made a name for himself in the smoky, intellectual comedy clubs of Greenwich Village.

His nervous, self-deprecating humor—filled with existential dread, relationship neuroses, and razor-sharp wit—set him apart from the era’s traditional comedians. But while he was quickly becoming a stand-up star, Allen had bigger ambitions. He wanted to write and create on his own terms, not just tell jokes in nightclubs.

Allen’s first brush with the film industry came in 1965 when he was hired to write the screenplay for What’s New Pussycat?, a madcap sex comedy starring Peter O’Toole, Peter Sellers, and Romy Schneider.

The film, about a womanizing writer who seeks help from a bizarre psychiatrist, was originally meant to be a light Hollywood romp, but with Allen’s touch, it became something entirely different—neurotic, absurd, and full of witty dialogue.

However, the experience was far from ideal for Allen. Hollywood producers rewrote much of his script, and Peter Sellers’ rising influence changed the film’s direction. Though it became a box-office hit, Allen walked away frustrated. If he was going to write movies, he needed full creative control.

Despite his frustrations, What’s New Pussycat? did something crucial—it introduced Woody Allen as a screen presence. His supporting role in the film as a neurotic side character resonated with audiences, and suddenly, he wasn’t just a behind-the-scenes writer. He was on screen, bringing his nervous intellectual persona to life.

Hollywood saw potential. Soon after, Allen was given another opportunity—but this time, it was something even stranger.

In a bold and unconventional move, Allen took a low-budget Japanese spy film (Kokusai himitsu keisatsu: Kagi no kagi) and completely rewrote the dialogue, dubbing it over with a ridiculous new storyline about spies searching for a secret egg salad recipe.

The result was What’s Up, Tiger Lily? (1966), a surreal, absurdist comedy that was entirely unique for its time. The film became a cult hit, proving that Allen’s humor could translate to cinema—but he still hadn’t made a film that was truly his own.

Frustrated by his lack of control, Allen finally made the leap to directing with Take the Money and Run (1969), a mockumentary about an incompetent criminal named Virgil Starkwell. Shot in a faux-documentary style, the film blended absurd humor with slapstick and clever satire—establishing the comedic style that would define his early career.

Unlike his previous Hollywood experiences, Take the Money and Run was all Woody Allen. He co-wrote, directed, and starred in the film, ensuring that his voice was intact. Though modestly budgeted, the film was a hit, winning over critics and audiences alike.

More importantly, it proved that Allen could handle full creative control, paving the way for what would become one of the most distinctive and celebrated careers in cinema.

With Take the Money and Run, Woody Allen had arrived as a filmmaker. The 1970s would see him refine his style, shifting from pure slapstick to more sophisticated, character-driven comedies like Bananas (1971), Sleeper (1973), and Love and Death (1975).

And then, in 1977, he would create his masterpiece—Annie Hall, the film that changed romantic comedies forever and cemented his place in cinematic history.

By the dawn of the 1970s, Woody Allen had firmly established himself as a filmmaker. With the success of Take the Money and Run (1969), he proved that his distinctive blend of absurdity, satire, and neurotic humor could work in cinema. But while the film was a hit, it was still largely a slapstick-driven comedy. Allen, always restless and evolving, was about to refine his voice and take his place among the greats.

Allen’s next few films followed a similar pattern—self-contained comedic adventures where he played variations of his neurotic, bumbling persona.

By this point, Woody Allen had become one of the most unique comedic filmmakers in Hollywood. But something was changing. His films, while still absurd, were becoming more sophisticated, with sharper writing and deeper character work. And then came Love and Death (1975)—a turning point.

Love and Death was Allen’s first real attempt at a more mature, literary comedy. A parody of Russian literature, it combined existential philosophy, historical satire, and slapstick humor. While still zany, it hinted at Allen’s growing ambition—he was starting to experiment with themes of love, mortality, and the human condition.

Critics noticed. Audiences responded. And Allen himself was ready for his next great leap.

Then came Annie Hall.

This was the film that transformed Woody Allen from a great comedian into one of cinema’s greatest auteurs. It wasn’t just a comedy—it was a deeply personal, semi-autobiographical exploration of love, memory, and relationships.

Allen played Alvy Singer, a neurotic comedian reflecting on his failed relationship with the charming but independent Annie Hall (played by Diane Keaton). The film broke new ground in storytelling:

Annie Hall won four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actress (Diane Keaton), and Best Original Screenplay. It also beat Star Wars for the top Oscar—an astonishing feat.

This film redefined the romantic comedy genre and solidified Woody Allen as a filmmaker with profound insight into human relationships.

After Annie Hall, Allen moved even further into serious filmmaking. He became heavily influenced by Swedish director Ingmar Bergman, known for his existential dramas about life and death. This influence was seen in:

By the end of the 1970s, Woody Allen had completely transformed. No longer just a comedian, he was now one of the most respected filmmakers of his generation—balancing humor with deep explorations of love, philosophy, and the human psyche.

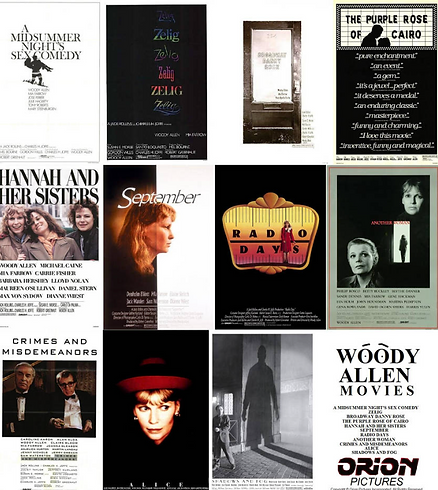

By the time the 1980s arrived, Woody Allen had already cemented himself as one of the most unique voices in American cinema. He had mastered comedy, revolutionized the romantic comedy genre with Annie Hall (1977), and proven his ability to craft serious drama with Interiors (1978).

But rather than settle into one style, Allen spent the 1980s experimenting—sometimes leaning into his Bergman-inspired dramatic side, other times returning to his comedic roots, often blending the two. This decade would be one of his richest, most diverse creative periods.

Allen started the decade on a reflective note, oscillating between comedy and introspection.

While these films were important stepping stones, his true masterpieces of the decade were just around the corner.

This period saw Allen reaching new artistic heights, blending humor, drama, and philosophy in ways that had never been done before.

This era solidified Allen’s ability to blend comedy with profound emotional depth. He was no longer just a comedic filmmaker—he was a true storyteller of the human experience.

As the decade drew to a close, Allen continued to refine his storytelling, fully embracing his dramatic side.

By the end of the decade, Woody Allen had proven himself more than just a comedic filmmaker—he was one of the most introspective and daring directors of his generation. His ability to mix humor, drama, fantasy, and philosophy made his work unparalleled in Hollywood.

As the 1990s dawned, Woody Allen stood atop the cinematic world as one of the most respected and prolific filmmakers of his time. He had revolutionized romantic comedies with Annie Hall, redefined neurotic humor in film, and crafted deeply philosophical dramas that blurred the line between comedy and tragedy.

Unlike many filmmakers who burn out or fade into repetition, Allen continued evolving, challenging himself, and creating at a relentless pace.

But the 1990s would also test him like never before—both professionally and personally. And yet, against all odds, he endured. His legacy, love for storytelling, and commitment to his craft remained unshakable.

The decade began with a controversial storm. His highly publicized personal life exploded in the media, nearly derailing his career entirely.

In 1992, allegations of misconduct surfaced, leading to an ugly legal battle between Allen and Mia Farrow. The scandal dominated headlines and divided Hollywood, yet Allen refused to be defined by it. He did what he had always done—he kept making movies.

Key Films of the 1990s:

Despite being blacklisted by parts of Hollywood, Allen never stopped. He doubled down on what made him great—deep, meaningful storytelling intertwined with humor and existential philosophy.

With Hollywood growing increasingly wary of his personal controversies, Allen turned his creative gaze overseas. He left behind the neurotic intellectuals of New York and embarked on a European filmmaking renaissance, delivering some of his most visually stunning and thematically rich films in decades.

Key Films of the 2000s:

This period solidified Allen’s ability to transcend eras, styles, and even continents. He was no longer just an American filmmaker—he had become a truly global storyteller.

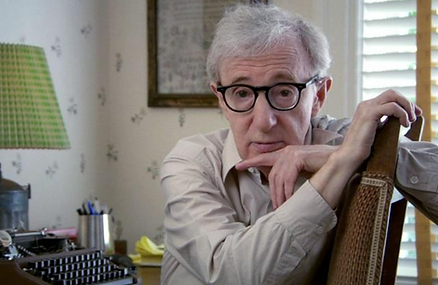

As he entered his late 70s and 80s, most would expect Allen to slow down. But instead, he doubled his creative output, churning out a film nearly every single year—a feat that no other living filmmaker of his stature has accomplished.

Key Films of the 2010s:

Even in his later years, Allen continued to produce intelligent, thought-provoking films. While his public image remained divisive, his artistic voice never wavered.

Now in his late 80s, Allen remains active, still directing, still writing, still pushing forward. His recent films, such as Rifkin’s Festival (2020), may not have the same cultural impact as Annie Hall or Manhattan, but they serve as a reminder that his passion for storytelling has never faded.

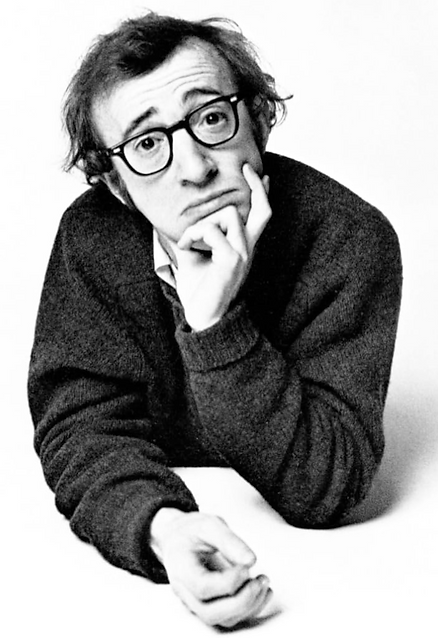

1. Relentless Creative OutputAllen has directed over 50 films in his career, often writing, directing, and starring in them himself. Few filmmakers—if any—have maintained such a consistent level of output and quality for six decades.

2. Blending Comedy and Philosophy Like No One ElseNo other filmmaker has been able to seamlessly merge deep existential themes with side-splitting humor the way Allen has. His films aren’t just funny—they are introspective, intellectual, and deeply human.

3. Reinventing the Romantic ComedyWithout Annie Hall, the modern romantic comedy as we know it wouldn’t exist. He redefined how relationships are portrayed in film, influencing generations of filmmakers from Noah Baumbach to Wes Anderson to Greta Gerwig.

4. Pioneering the Neurotic, Intellectual ProtagonistThe character of the anxious, neurotic, overthinking intellectual is now a staple of modern cinema and TV (think Curb Your Enthusiasm, Seinfeld, Louie). But no one did it before Woody.

5. Turning New York City into a Cinematic CharacterJust as Fellini immortalized Rome and Truffaut captured Paris, Allen turned New York into a living, breathing character in his films. His depictions of the city in Manhattan, Annie Hall, and Hannah and Her Sisters remain some of the most iconic in film history.

6. Surviving and Creating Despite ControversyFew filmmakers have been as publicly vilified as Allen. And yet, unlike others who faded into obscurity, he never stopped creating. His commitment to his craft, despite personal and professional exile, is something no other filmmaker has experienced—and never will.

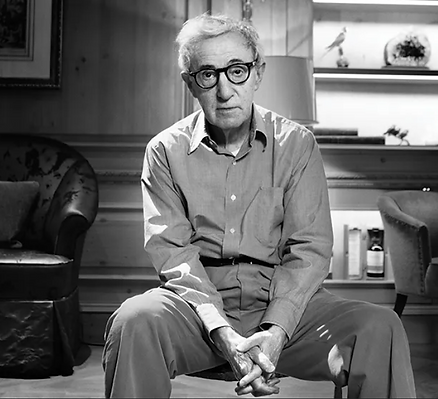

Woody Allen’s legacy is as complex as the characters he writes. Some see him as a comedic genius, a cinematic philosopher, and one of the greatest filmmakers of all time.

Others see him as a controversial figure whose personal life overshadowed his work.

But one thing is undeniable:No other filmmaker, comedian, or writer has created such an extensive, intelligent, and enduring body of work. And no one ever will.

He is, and will always be, one of a kind.