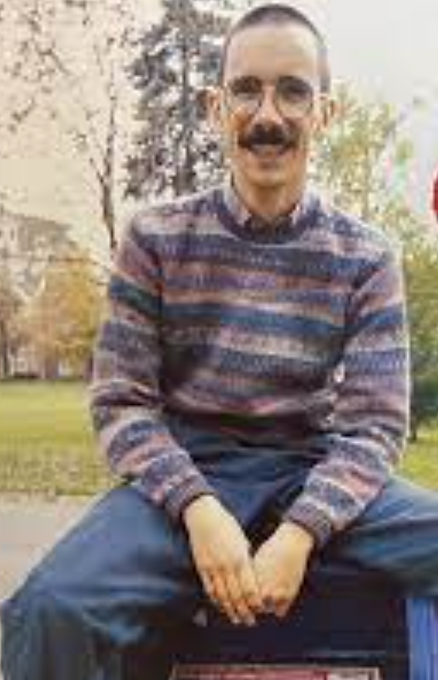

Bill Watterson’s journey to Calvin and Hobbes is a fascinating story of perseverance, artistic integrity, and an unwavering commitment to creativity.

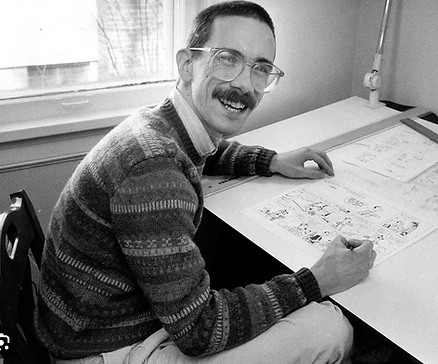

Born on July 5, 1958, in Washington, D.C., Watterson grew up in Chagrin Falls, Ohio. As a child, he loved drawing and found early inspiration in newspaper comics like Pogo by Walt Kelly and Peanuts by Charles Schulz. His parents, particularly his father (a patent attorney), supported his creativity but also encouraged him to consider a practical career path.

In 1976, he enrolled at Kenyon College in Ohio, where he studied political science, but his passion for cartooning never faded. He became the editorial cartoonist for the college newspaper, where he honed his ability to mix humor with sharp observations about society.

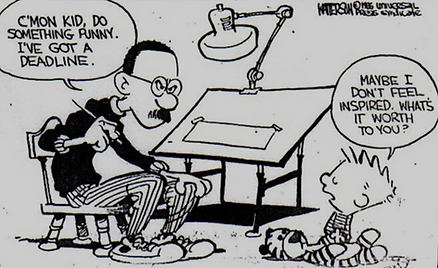

After graduating in 1980, Watterson landed a job as an editorial cartoonist for The Cincinnati Post. However, he quickly found the work restrictive and uninspiring. His job lasted only a few months before he was let go. Determined to make it as a cartoonist, he moved back home and spent the next few years creating comic strip concepts and submitting them to newspaper syndicates.

He faced rejection after rejection. Syndicates either disliked his style, felt his humor was too intellectual, or didn’t see commercial potential. He experimented with different ideas, including one about a side character named Calvin, a mischievous young boy.

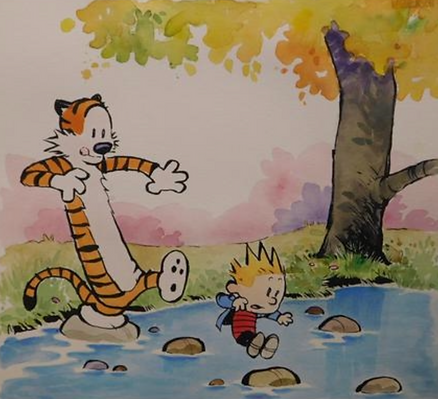

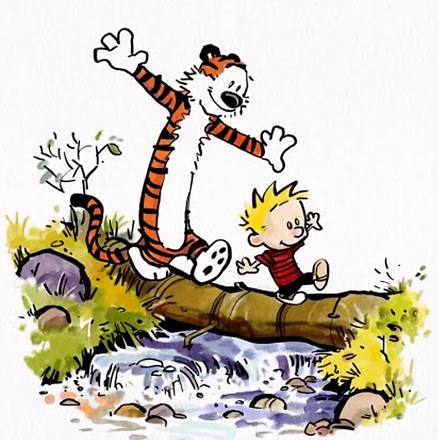

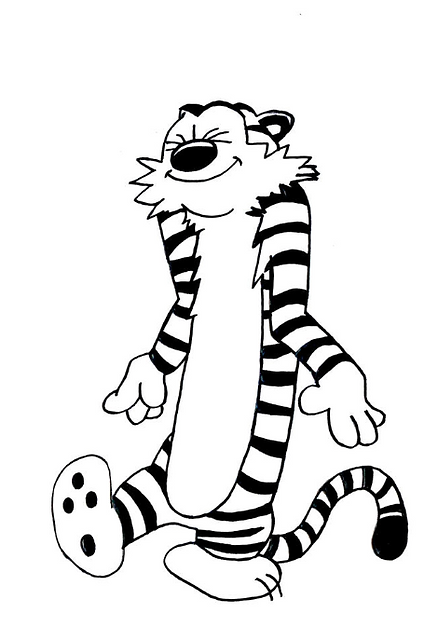

While developing various comic strip ideas, Watterson realized that the dynamic between Calvin and his stuffed tiger, Hobbes, was the most compelling part of his work. He built a world around their relationship, where Hobbes appeared as a real tiger to Calvin but as a stuffed animal to everyone else—a brilliant metaphor for the power of imagination.

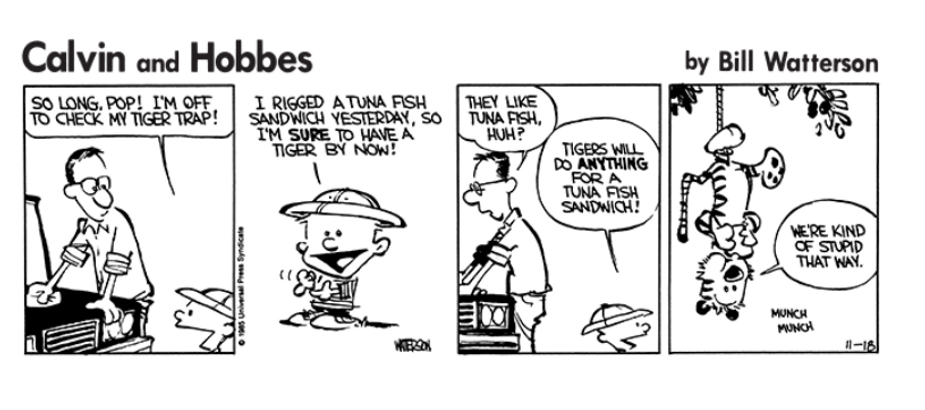

In 1985, after years of rejection, Universal Press Syndicate finally accepted Calvin and Hobbes. The strip made its debut on November 18, 1985, in 35 newspapers. Watterson’s sharp humor, philosophical depth, and beautifully drawn panels quickly captivated readers.

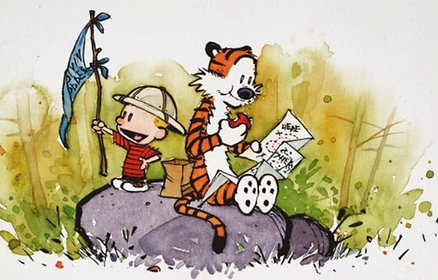

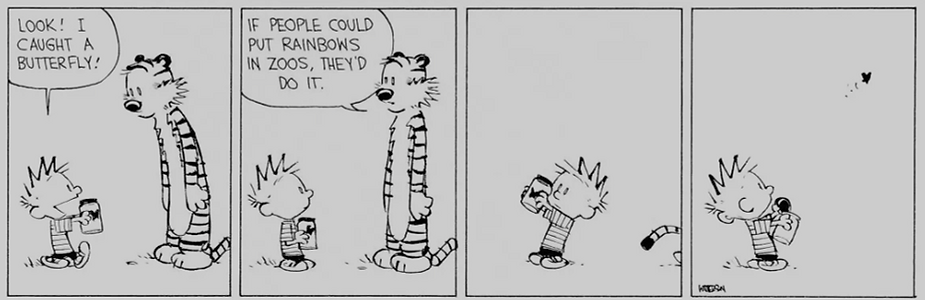

Within a few years, Calvin and Hobbes exploded in popularity. Watterson's refusal to dumb down his humor, combined with his detailed artwork and deep storytelling, made the strip stand out. He used the comic to explore everything from childhood imagination to societal absurdities, environmentalism, and existential questions—all through the lens of a mischievous six-year-old and his fiercely independent tiger.

Despite his success, Watterson famously resisted commercializing Calvin and Hobbes. He fought syndicates that wanted to turn his characters into plush toys and greeting cards, believing that it would cheapen their integrity. His commitment to artistic purity became legendary.

By the early ’90s, Calvin and Hobbes was a cultural phenomenon, appearing in over 2,400 newspapers worldwide. It became one of the most beloved comic strips of all time, cementing Watterson’s place in the history of comics.

When Calvin and Hobbes debuted on November 18, 1985, in just 35 newspapers, few could have predicted the impact it would have on the world of comic strips. Over the next decade, Bill Watterson’s creation would become one of the most beloved and influential comics of all time, reaching millions of readers worldwide.

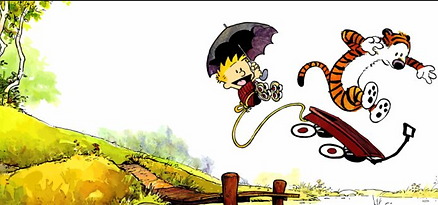

The strip immediately stood out with its blend of childhood mischief, deep philosophy, and stunning artwork. Calvin, the six-year-old protagonist, embodied boundless imagination and irreverence, while Hobbes, his stuffed tiger who came to life in Calvin’s mind, provided a perfect foil—playful, wise, and at times skeptical of Calvin’s antics.

Readers quickly fell in love with Calvin’s wild fantasies—whether he was Spaceman Spiff, Tracer Bullet, or a prehistoric dinosaur—and the deep conversations he had with Hobbes about life, school, and the absurdities of the adult world. By 1987, Calvin and Hobbes had been picked up by hundreds of newspapers, and fan enthusiasm was growing rapidly.

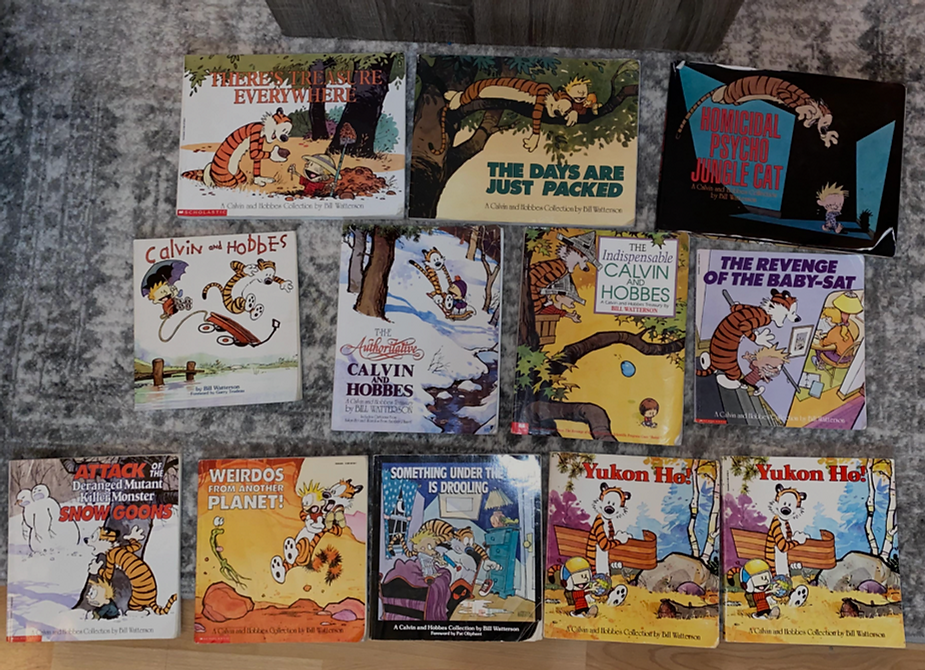

The release of the first Calvin and Hobbes book collection in 1987 was a massive success, propelling the comic to even greater heights. More readers discovered the strip through the books, fueling demand. Watterson’s storytelling evolved, incorporating ambitious Sunday strip layouts that pushed the boundaries of newspaper comics.

His artistic inspirations, including Pogo by Walt Kelly and Krazy Kat by George Herriman, became more evident. Watterson experimented with visual composition, panel layouts, and intricate backgrounds, elevating Calvin and Hobbes beyond the traditional constraints of daily comics. By 1988, the strip was appearing in over 600 newspapers, and its book collections were bestsellers.

As Calvin and Hobbes grew, newspaper syndicates pressured Watterson to commercialize the characters. They wanted plush toys, T-shirts, animated specials—anything that could bring in more money.

But Watterson fiercely resisted, arguing that mass marketing would cheapen the artistic integrity of the strip.

His battle with Universal Press Syndicate escalated, culminating in a contractual dispute that forced him to take a nine-month hiatus in 1991. When he returned in 1992, he had won unprecedented control over his work, including the right to dictate how his Sunday strips would be printed—allowing for more dynamic, full-page layouts.

By the early ’90s, Calvin and Hobbes was a global phenomenon, appearing in over 2,400 newspapers and selling millions of books. Watterson continued to push creative boundaries, incorporating more artistic flourishes, surreal sequences, and philosophical depth.

The strip resonated with all ages—kids saw their own wild imaginations reflected in Calvin, while adults recognized the strip’s deeper messages about society, creativity, and the loss of childhood wonder.

Despite overwhelming popularity, Watterson remained a recluse, refusing interviews and maintaining a mysterious aura. His refusal to merchandise Calvin and Hobbes only added to its legendary status—fans could only experience it through the comics themselves, keeping the magic intact.

By the mid-1990s, Calvin and Hobbes had become one of the most beloved comic strips of all time. It was a cultural touchstone, appearing in over 2,400 newspapers worldwide, with book collections consistently topping bestseller lists. And yet, at the peak of its success, Bill Watterson made a shocking decision—he walked away.

On November 9, 1995, Watterson announced in a letter to newspaper editors that he would be ending the strip on December 31, 1995. His reasoning was simple yet profound:

"I believe I’ve done what I can do within the constraints of daily deadlines and small panels. I am eager to work at a more thoughtful pace, with fewer artistic compromises."

Unlike many cartoonists who continued their work indefinitely or passed their creations on to assistants, Watterson had no interest in diluting Calvin and Hobbes. He saw it as a complete artistic work rather than an ongoing franchise. Ending it on his own terms ensured that it would remain pure, untouched by overextension or commercialization.

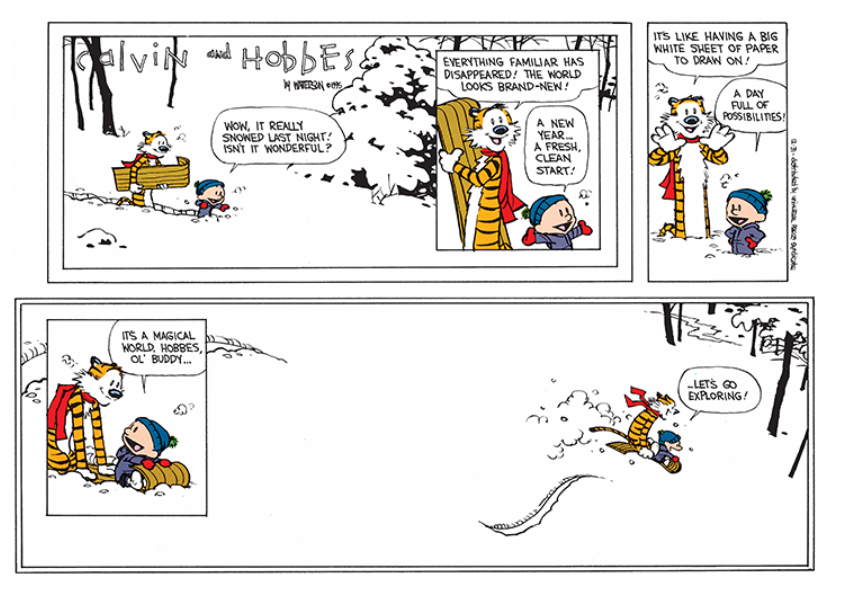

The last Calvin and Hobbes strip was a perfect sendoff. Instead of a dramatic farewell, Watterson crafted a simple, poetic conclusion:

Calvin and Hobbes wake up to a world blanketed in fresh snow."It’s a magical world, Hobbes, ol’ buddy... let’s go exploring!"They sled off into the white unknown, leaving readers with a sense of wonder and endless possibility.

Unlike many comic strips that fade into irrelevance or limp to an unceremonious end, Calvin and Hobbes left on the highest possible note, securing its legacy as an untouchable masterpiece.

After retiring the strip, Watterson disappeared from the public eye. He retreated to a quiet life in Ohio, painting for his own pleasure and avoiding the limelight. He rarely gave interviews and remained firm in his decision to keep Calvin and Hobbes free from commercialization.

In 2014, he made a surprise return to comics by guest-drawing a few strips for Pearls Before Swine, but otherwise, he has stayed out of the public sphere.

In 2023, Watterson released The Mysteries, his first major artistic work in decades—a dark, philosophical illustrated book that was starkly different from Calvin and Hobbes.

Despite ending nearly 30 years ago, Calvin and Hobbes continues to inspire generations of readers. Its themes—imagination, childhood wonder, existential musings—are timeless. Because Watterson refused to commercialize it, the strip remains an untouched work of art, immune to dilution.

There will never be another Calvin and Hobbes because no one else has Watterson’s combination of artistic mastery, storytelling depth, and absolute commitment to integrity. He created something perfect—and then he let it go.

Even though Calvin and Hobbes ended in 1995, its impact on art, literature, and pop culture continues to be profound. Many artists, cartoonists, and storytellers have cited Bill Watterson as a major inspiration, and elements of his work can be seen in everything from modern webcomics to animated films.

Many contemporary cartoonists have been deeply influenced by Watterson’s artistic style, humor, and storytelling techniques:

Many comic strips today, from Zits to Big Nate, owe some of their playful humor and character-driven storytelling to Calvin and Hobbes.

Watterson’s ability to capture childhood imagination has resonated in animated films, particularly those that explore the power of wonder and creativity:

Even though Calvin and Hobbes was never adapted into an animated series (because Watterson refused to commercialize it), its influence can be seen in the best modern animation that celebrates imagination and childhood.

The writing in Calvin and Hobbes—both comedic and philosophical—has shaped many authors who grew up with it:

The strip’s ability to weave deep existential questions into everyday life has given countless writers a blueprint for storytelling that balances humor and wisdom.

Perhaps Watterson’s biggest legacy is his refusal to compromise his art for money. His stance against commercialization inspired generations of independent artists to fight for creative control over their work.

Even though Calvin and Hobbes remains frozen in time, its influence is alive in comics, animation, literature, and creative industries that value artistic freedom. Watterson’s dedication to his vision has inspired countless creators to fight for their own artistic integrity, proving that sometimes, saying “no” to commercialism is the most powerful statement an artist can make.

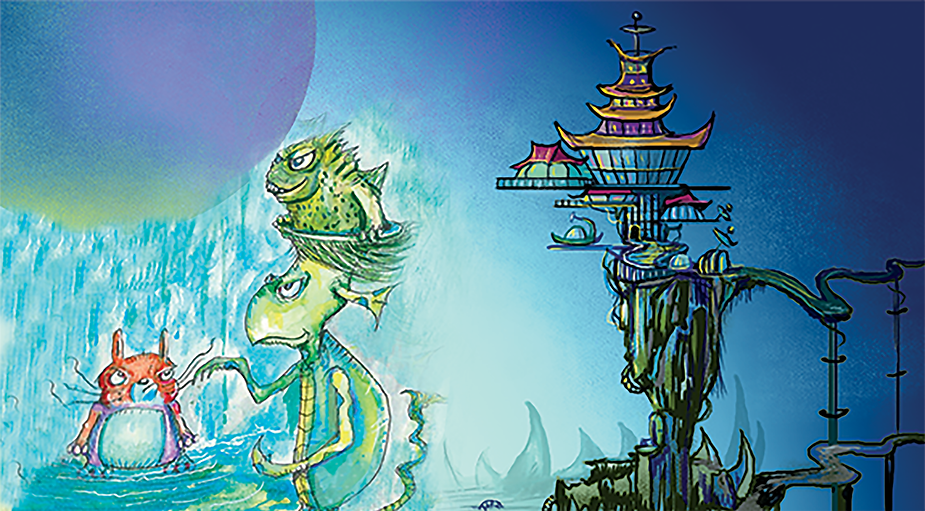

with Matsuverse, the FunkyIPuppets, and Yokai-inspired story has a deep creative and philosophical core—one that resonates strongly with the spirit of Calvin and Hobbes. While Matsu world blends music, technology, interdimensional travel, and ancient traditions, Matsu shares key thematic and artistic DNA with Bill Watterson’s work. Here’s how:

At its heart, Calvin and Hobbes was about the boundless imagination of a child, where a simple cardboard box became a time machine, and a stuffed tiger was a best friend.

One of Watterson’s greatest strengths was his ability to infuse philosophy, existential questions, and social critique into a comic strip without losing its humor or charm.

Calvin and Hobbes was, at its core, about the relationship between a boy and his tiger—a connection that was both real and unreal at the same time.

Watterson pushed the boundaries of what a comic strip could be, using cinematic perspectives, expansive landscapes, and wildly creative panel structures to tell stories that felt larger than the small space they occupied in a newspaper.

Calvin and Hobbes wasn’t just a comic—it was a movement, a philosophy, a challenge to what could be done in a limited medium. Your work with Matsu and the FunkyIPuppets is shaping up to be the same.